Colson Whitehead: Apex Hides the Hurt

“Was struggle the highest point of human achievement? No. But it was the point past which we could not progress, and a summit in that way.”

Apex Hides the Hurt is an apple, a Granny Smith. It’s tart and crisp, a little sting to the cut on your lip, and a little pleasure in the pain. This book was recommended to me by someone like a Granny Smith apple, and that might be why I let the recommendation sit for a long time in an open browser window on my phone. I knew I’d like it, and that the enjoyment would have a tinge. My conversations with this person often hinged on identity, on what it means to lead, on how, in our different ways, we worked toward personal and collective liberation, even as we both felt stuck.

I’m glad I waited until this moment to read it: a moment in American history that asks us to think hard about names, about choices, about what “America” means and how we take action around that name. “Girl, I told you,” responded the person who recommended it when I thanked him, crisp and memorable and just what I expected when I bit.

Assata Shakur: Assata

“Once you understand something about the history of a people, their heroes, their hardships and their sacrifices, it’s easier to struggle with them, to support their struggle. For a lot of people in this country, people who live in other places have no faces. And this is the way the u.s. government wants it to be.”

Assata is your morning cup of coffee—it’s the jolt you need, every day, to stay engaged, to fight, to remember what you’re fighting for, who you’re honoring. I could have pulled any quote from this book, published in the eighties, and it would have been equally resonant. We are living in a present that brings the past back day by day, and if we are truly aware, we know that our only option is to fight like hell against it.

I love coffee. I wake up at dawn to enjoy two cups on the couch, where I snuggle with my cat before my day begins. The waking up can be slow, and has been—when people at political or resistance meetings these days ask me why I’m there, I usually say, “I feel like I took thirty years off. Now I’m on.” In waking, we have no choice but to face our world, to dive in. Have your coffee: read this book.

Marlon James: A Brief History of Seven Killings

“The dream didn’t leave, people just don’t know a nightmare when they right in the middle of one.”

A Brief History of Seven Killings is a bayonet, and not because of its piercing language or the violence it contains. It’s a bayonet because it seems, to me, like it comes from a different world entirely than the one I’ve spent 35 years inhabiting. The bayonet was in use not that long ago, and James’s book takes place more recently even than that, and in places familiar to me. But the surprising language, the incredible characters, and yes, the violence, might as well take place on a different planet. They’re not, in general, characters that I can imagine easily, though that doesn’t keep me from identifying with them.

It’s like when you see bayonets in old paintings: you can feel the fear, the imminent suffering. You can see the impossible choices while knowing that they are choices you’ll never have to make. The book triumphs for this reason: we are all these characters, even if we’ve never held a bayonet, never been to Jamaica, never had to make a truly impossible choice.

Lauren Groff: Fates and Furies

“It occurred to her then that life was conical in shape, the past broadening beyond the sharp point of the lived moment. The more life you had, the more the base expanded, so that the wounds and treasons that were nearly imperceptible when they happened stretched like tiny dots on a balloon slowly blown up.”

Fates and Furies is a suitcase, something you pack differently each time, but also a container in which we feel past vacations. The wear and tear, the outer being of it, never changes, not much. But it’s what’s inside, what seems to matter this time, that is always pushing the suitcase forward. The outer and inner, the different experience of the same item, that’s this book, the same story told twice, the inner and outer from both perspectives. It works because it requires incredible perspective, pulling back and panning around before zooming in.

It’s easy to swap perspectives in writing, to embrace the push and pull, but Groff does a particularly beautiful job with the crevasses, the deep pockets that have a single earring stuck at the bottom, a piece of yarn stuck in the wheel. It’s in these details that the story is fulfilled, the way you see a suitcase coming around the conveyer belt and know that it’s yours, know what’s inside, know what’s causing the bulge.

Emily St. John Mandel: Station Eleven

“None of the older Symphony members knew much about science, which was frankly maddening given how much time these people had had to look things up on the Internet before the world ended.”

Station Eleven is a disk defragmenting. It takes a diffuse idea – what if the world actually did end – and makes some kind of order from it. Mandel’s language is like the language of a computer in that it is particular and beautiful, economic and at times austere. I imagine her germinating the idea, living with the characters and the concept as she put them together, one piece at a time, comic, flu, symphony, and the result is this beautiful, strange, important work, which runs like a dream, with a momentum I’ve only dreamed of having in my own writing.

There are so many post-apocalyptic novels out there, like there are so many ways to solve computer problems. But sometimes the solution is just about organization, not fixing per se, just like Station Eleven is built around an incredibly stark, believable reality: order and chaos at once, like our disks, our realities, our memories.

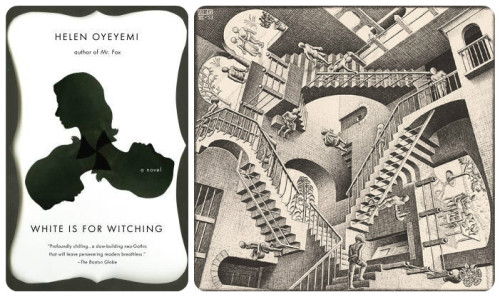

Helen Oyeyemi: White is for Witching

“Occasionally, to tease her for walking slowly, I’d put a hand to the small of her back and gently push her forward. Whenever I did, her hair swished over my fingers like torn silk. I felt this more than once, but I can’t explain it. Her hair only came down to her shoulders, but when I couldn’t see her clearly, her hair was very long.”

White is for Witching is an M.C. Escher painting. At first, its mystery is plain and unintelligible, then you think you’ve figured it out: the connection is here, is this, you think. And then you realize, no, it’s not quite what I thought, is it? You sit back again, pretending you’ve got it all figured, but you don’t.

And even if you do, the intricacy, the creativity it took to come up with that idea – it’s pretty impressive, you have to admit. The same is true of this book: the ins are outs, the outs are ins, the characters are so complex that they seem to upend one another and our ideas of what is real altogether. The concrete and mystical co-exist as if nothing else could be more normal, and that’s what’s magical about it, just like Escher.

Hanya Yanigihara: A Little Life

“Why wasn’t friendship as good as a relationship? Why wasn’t it even better? It was two people who remained together, day after day, bound not by sex or physical attraction or money or children or property, but only by the shared agreement to keep going, the mutual dedication to a union that could never be codified.”

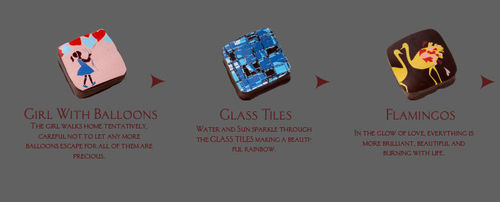

A rainbow is so many things: a child’s drawing, a miracle in nature, a potent symbol. This one happened in my office, where I spend a lot of time looking out the window, checking on the weather or seeing if the mountains are out. We are moved by rainbows, aren’t we? I am, and I think it’s for all of these reasons, social, natural, symbolic.

A Little Life does something similar to a rainbow for readers. Reading ends, but this book asks us to search far beyond its pages, to look harder and deeper for meaning. Not a lot is clearer at the end of the book than the beginning, and I think it’s safe to say this would be equally true if the end of a rainbow appeared. We both know there’s no pot of gold there – it is itself gold.

Jenny Offill: Dept. of Speculation

“She says every marriage is jerry-rigged. Even the ones that look reasonable from the outside are held together inside with chewing gum and wire and string.”

If Speedboat is skagit gneiss, then Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation is horsehair plaster. This is to say, the two books are related: both spare, both asking the reader to fill in a lot of details, both interested in being a woman in New York. But Speedboat’s density made it difficult for me, while Dept. of Speculation has a clearer narrative, on the reader can grasp and hold onto for the duration of the book.

Over the summer, in the mountains of the North Cascades, the rock was so hard, so impossible, that one prospector’s crew quit trying to build a road after only one day. Now, now that I am back in Providence, I’m living in an old Victorian house, one with horsehair plaster walls, and the nails I hammer to hang my art slip right back out. The plaster crumbles to dust in my hands. This plaster, the ease of getting through it, is that narrative, the one you don’t have to fight through. We get everything we need, nothing extra, and that is just enough.

Brian Doyle: Children and Other Wild Animals

“Maybe we should sue ourselves, for assault and battery, for theft, for rape in the first degree. Do other species have standing in the courts of human beings? Can osprey testify about their near-death experience, when they were poisoned en masse, and parents were forced to watch as their babies hatched too soon, inside their translucent useless eggshells, and died sobbing for breath, their bones unknit, unable even to mew, unable to see even a shard of the light hatched in the furnaces of the stars? What about trees? Or the thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands and thousands of kinds of beings slain along the way as we scrabbled for food and money and bigger cars? Or the thousands and thousands of kinds of beings we will never even see or hear or identify or gape at or marvel over who will vanish in their homes in the seething sea, in the misty canopy, in the volcanic vent?”

This is a much longer quote than I often post, I know. But it’s important, like oatmeal: so good for you, so varied, a food you could change up and eat for practically every meal.

You don’t though. Why not? Because oatmeal gets, well, a little exhausting after a while, doesn’t it? Children and Other Wild Animals is a book of rather short essays, and taken alone, they are beautiful. Some, I think, near perfection, such as Joyas Volardores, which I teach every semester for its beauty, its voice, its attention to detail in research.

However, reading them all together, all at once, it’s like eating nothing but oatmeal: the message gets obscured a little bit, the earnestness feels slightly forced, in moments. How can he love so much, so deeply, and so unfailingly? He doesn’t – as he reminds us in the essays – but it’s easy to read past that. Sometimes we all need a frozen Snickers bar or a pile of greasy fries. And these essays, I think, are best taken like oatmeal: regularly, but not exclusively.

Brian James: Pure Sunshine

“It’s not like we were infatuated with death or that we were depressed in any unusual way. It was just that the prospect of living a long life seemed like such a chore.”

Pure Sunshine is my tragus piercing. I got it when I was nineteen, when everything felt so important and inevitable, when my life was just beginning and a piercing felt like a big event. I got in trouble for piercing my cartilage (note: no earring in that piercing these days), and the next year, when I was living on my own, nineteen and reckless and full of emotion, I got this piercing. I did it on St. Mark’s, at a shop where my friend got barbells through the back of her neck, where nipples and eyebrows and lips were pierced regularly.

Be brave, I told myself when the man came at me with a needle. This doesn’t matter that much. Pure Sunshine is all about this time of life: when immaterial mingles with vital at every turn, when you feel your smallness in the world but you also feel your own essential self, more when you do drugs and live through it, more when you stay awake all night for the thrill, more when you figure out a train system or a city’s grid. Now, I sometimes fiddle with my tragus piercing, sometimes change the jewelry. But it doesn’t change anything about my life, and it never has, except for those first few months after I got it, when it meant something important, when almost everything stood for a symbol of independence.

Lydia Millet: Mermaids in Paradise

“It’s frowned upon to say so, but if we’re being honest, come on – please. There are currently billions of humans. Even allowing for some repetition, are there billions of reasons for being?”

Mermaids in Paradise is a brand new pair of white shoes. Or a white dress, or a tablecloth, anything obviously doomed. Any book that you’re promised will be a laugh a minute is doomed in this way, and while the beginning lives up to the high praise, very soon, the narrative flags, the characters begin to look like caricatures, and the reader must simply push through. It’s like seeing the first scuff on those new shoes and thinking, “Well, I guess I should have known this was coming.”

I won’t spoil the book, in case you want to read it, but the final pages were, to me, maddening beyond compare. I talked about this book to my undergraduates, holding it up, saying, “Here’s an example of that thing I told you never to do.” Somehow, Millet gets away with it. I was so glad to reach the end, snickering here and there but mostly disappointed, and then wham! The reader gets a smack on the head. Maybe it’s what she intended, but if so, I don’t understand the purpose of lulling a reader in that way, only to shock and anger them at the end. It’s inevitable, I guess, that the shoes get thrown out sooner, that they end up filthy and beyond repair, no matter how many times you’ve tried running them through the wash.

Renata Adler: Speedboat

“The idea of hostages is very deep. Becoming pregnant is taking a hostage – as is running a pawnshop, being a bank, receiving a letter, taking a photograph, or listening to a confidence. Every love story, every commercial trade, every secret, every matter in which trust is involved, is a gentle transaction of hostages.”

Speedboat is Skagit gneiss. You pronounce it “nice,” like it’s a rock you’ve wanted to talk to all your life. I’m here in the Pacific Northwest, in North Cascades National Park, working for the summer as a tour guide, telling people about how hard this rock is, and how only one visionary, JD Ross, the father of Seattle City Light, the public electric company, could imagine and bring to fruition a hydroelectric project that cut through this terribly difficult substance. It was another thirty years before they built a national park right around his three gigantic powerhouses and dams.

I don’t know that I am smart enough for Speedboat. I wanted to read it because it’s on all the non-traditional narrative reading lists, because it’s unusual in form in a way I thought I’d love. But like Skagit gneiss, I found it dense and difficult, hard to get through and find something inside of. I’m not the JD Ross of Speedboat, and I’m realizing, both from reading this book and from the difficult hours of my job, that this is okay: I don’t have to understand or like everything. BUT! I want to know more people who did read and like this book, so if that’s you, tell me: what was your experience? How did it feel?

Also, the most popular joke here: “What did the Geologist say?” “Gneisssss!”

Helen Oyeyemi: Boy, Snow, Bird

“The places you go to, do you see colored people? Let me answer that for you. You see them rarely, if at all. You’re trying to remember, but the truth is they don’t exist for you. You go to the opera house and the only colored person you see is the stagehand, scattering sawdust or rice powder or whatever it is that stops the dancers slipping … folks would look at him pretty hard if he was sitting in the audience, they’d wonder what he was up to, what he was trying to be, but being there to keep the dancers from slipping is a better reason for him to be there, he’s working, so nobody notices him but me.”

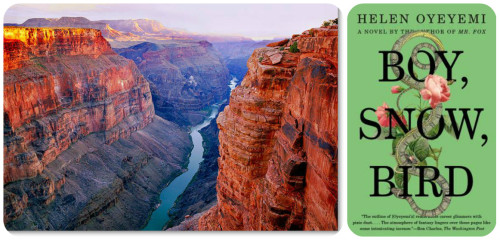

Helen Oyeyemi’s Boy, Snow, Bird is the Grand Canyon. I’d heard about it for years, thought, “Oh, I should read that,” and then forgot about it, having something else on my nightstand, some other marvel or practicality taking priority. I haven’t been to the Grand Canyon, but I imagine that, like Boy, Snow, Bird, there are views that take your breath away even if you know that they will, even if you know what you’ll see, as you know the backbone of Snow White. I’d bet it’s impossible to anticipate what you feel as you stand there. As I read this book, amazed at how impossibly beautiful some of the passages were, I was reminded of all the times I’ve been amazed by things I knew would be amazing: standing before the Berlin Wall, gazing at the Sistene Chapel, admiring Jerusalem from the city walls.

At the Grand Canyon, the only choice is to look down, and that’s why this book is that place, instead of a place I’ve been to – Oyeyemi asks the reader to look down, and in, and to plumb away, asking herself to see things as she hasn’t seen them before, and to take a closer look at why.

Allen Kurzweil: Whipping Boy

I slide the arrest sheet across the table, and Feiter slides it right back.

“Keep it,” he says.

“Are you sure?”

“Sure I’m sure. Add it to the collection. I had to deal with my own version of Cesar when I was a kid. I know how memories like that stay with you.”

Allen Kurzweil’s memoir Whipping Boy is a bypass road. My teacher Wendy Brenner writes in the craft book Show & Tell, “ Write about the subject which – for some reason that’s a mystery to all your friends, who are sick of hearing about it – obsesses you.” Kurzweil has found his subject, but it’s not what you’d think from that cover. Yes, he talks about the bully, but the vast majority of this book is spent on a major fraud his bully committed later in life along with some other lowlifes. The scam is breathtaking, it’s shocking and it obviously obsessed Kurzweil. But it’s so fully a different subject that the book gives itself over to the ideas of scam and scandal, not to the emotional heart of what it means to have a bully, and how that bully’s shadow remains, sometimes forever. Instead, we divert for, I’d argue, most of the book, into the thing that obsesses Kurzweil instead of the deep psychology I’d wished for when I opened this book. Had it been sold or marketed or titled differently, I would have happily read about a fraud committed by a distant acquaintance, but as it was, I felt like we were seeing the city from the highway, but were destined to make a wide berth around it.

Celeste Ng: Everything I Never Told You

“Above them, the sky rolled out a deep black, like a pool of ink, littered with stars. They were nothing like the stars in her science books, blurred and globby as drops of spit. They were razor-sharp, each one precise as a period, punctuating the sky with light."

Everything I Never Told You is an abacus. The abacus is a tool primarily used for accounting, and this story lives in its accounting: what caused Lydia’s death? What small – and large – acts led to a moment of such horror? Who’s to blame? The abacus moves forward and back, each bead autonomous, but each also part of a larger group: a row, a sum, a calculation. A sense of continuity imbues the abacus: this is an ancient object that we just can’t shake, even though we look at them historically most of the time these days.

The characters in Everything I Never Told You are the beads of the abacus – we move around with them in time and place. Celeste Ng steers us through their minds and lives, offering delicate and human motivations and working through the novel in present tense, past tense, even, a shocking and beautiful choice, future tense. Hers is the careful hand of the accountant: without her, the beads of the novel could slip, fall incorrectly, lead us to the wrong calculations, the wrong conclusion.

Benjamin Anastas: An Underachiever’s Diary

“My heart was full with her, but I lacked the means to express myself, other than the usual words, and tender actions, which seemed like an inherited wisdom to me, universal LOVE, the failing panacea of my parents’ generation: flower children, baby boomers, whatever name you’d like to use. Exactly what had the sexual revolution gained them, after all? Some measure of bodily happiness, a sex instinct unfettered, the herpes virus, the social acceptability of T-shirts and cutoff shorts, but what else? Had they really changed our values and attitudes?”

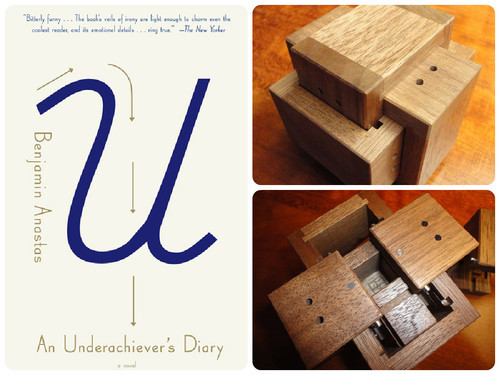

Benjamin Anastas’s An Underachiever’s Diary is a puzzle box. These boxes are crafted with incredible care, made to surprise and delight and sometimes, to hide things. Some puzzle boxes take hundreds of precise moves to open – slide a piece out and a different piece collapses in. Slide a piece in and watch another piece jut out. Anastas asks the reader to follow his character as he bumbles along, disappointing everyone in his path.

But at the core, when you work through the pieces, what’s inside the box? Nothing, except the satisfaction of having gotten there, and that is enough: Anastas is so tricky, he makes the reader proud to love WIlliam in spite of the alleged project of the book. His use of humor is perfect, heartbreaking and acerbic, and by the end, we love William just because of his mediocrity, for all his fumbles and for all the times we’ve seen those same ones in ourselves.

At a time when we tell all students that they’re overachievers by giving them ‘A’s when we should be giving 'B-’s or worse, what a relief it is to have underachievers in class. If not for them, the curve would look even more like a wave than a bell, and we’d all be bowled over.

Jesmyn Ward: Salvage the Bones

“A house sits in the middle of the track. It is yellow, and its windows have been blasted open by the storm, but its curtains remain. They flutter weakly. We climb around it, look east and west along the track, and see many houses lining it: it is a steel necklace with wooden beads.”

Salvage the Bones is a held breath. From its opening pages, the tension is high, and it stays that way as the clock ticks down to the coming storm. Ward’s ability to maintain this suspense while offering the reader an incredible variety of images is striking: she seems to offer release valves for the reader not through plot, but through her masterful use of language.

We hold our breath when we wait for something to happen, sometimes, or if we are underwater, or if we are doing a particularly hard exercise and forget that breathing will help, not hurt. We hold our breath without realizing it, and in a way, that’s how this book felt to me. As I read it, voraciously, without worrying about the obligations of my life, I could see, even as I didn’t know what would happen, that the climax would be beautiful and painful and as intense as the rest of the book, and that in order to reach it, all I could do was read. I’ve noticed, as a result of this book, that every time I finish a book, I let out a big sigh, sometimes accompanied by a “Hm.” Salvage the Bones got this treatment, though the sigh was as much for remembering to breathe as anything else.

Tom Perrotta: The Leftovers

“An odd sense of melancholy took hold of her – it was the same feeling she got walking past her old ballet school, or the soccer fields at Greenway Park – as if the world were a museum of memories, a collection of places she’d outgrown.”

The Leftovers is unlike so many books of magical realism because, like a balancing pose, it keeps a clear and narrow focus and remains deeply grounded at all times. The reader feels Perrotta leading her through the book. He understands all the parameters he’s created and knows what he’s left out. Like a balancing pose, what is most important is what remains on the ground, not the elevated – magical – portion. The stability, the realism, is what allows the magic to occur, and it’s what’s missing from so many books that have the goal that Perrotta has so fully achieved.

Jonathan Safran Foer: Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

“I thought about all of the things that everyone ever says to each other, and how everyone is going to die, whether it’s in a millisecond, or days, or months, or 76.5 years, if you were just born. Everything that’s born has to die, which means our lives are like skyscrapers. The smoke rises at different speeds, but they’re all on fire, and we’re all trapped.”

Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close is a light bulb. For so much of my life, I would learn about something in history and think to myself, “And they didn’t even have electricity.” In these moments, marveling at the abilities and creations of people who came before me, the ease of my own life, the ability to flip a switch, offered a kind of perspective I needed to remind myself of over and over.

The seminal event of my adult life happened when I was nineteen, when I moved to New York City on the first of September, 2001, after dropping out of college. The fear that swept through my life, and the lives of all New Yorkers and through America in the days and weeks after 9/11, is hard to overstate for me, because rarely have I felt so alone and so uncertain about the future.

But Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close reminded me that all adults have a seminal event in their lives. For my grandparents, that event was World War II, when millions, not thousands, of lives were lost. It’s hard to compare the two events, and many more lives have been lost as a result of that day in September, but for a moment, reading this book, I thought about my grandparents, all four of them, weeping when they saw the photos and read about concentration camps. I realized that when I’m old, I’ll be talking about 9/11 the way they talk about the Holocaust.

Jonathan Safran Foer’s narrators tell a story of 9/11 that is so much bigger than that day, and asks the reader to travel though time to understand something impossibly painful but deeply necessary, and this is what gives it power, and why I was afraid to read it for so long. I’m glad that I did, for the way I can see differently now. I know that the next time my dad rhapsodizes about Bob Dylan, I’ll hear something different in his voice.

Ruth Ozeki: A Tale For The Time Being

“Better to do battle with the waves, who may yet forgive me.”

A Tale For The Time Being is a local train. It makes all the stops: the ones where only a few people get out, the busy ones where you might transfer, if you weren’t already in a seat, if you got out at an express stop anyway, if you were going to the end of the line.

Some days, this thoroughness, this every stop commute, feels plodding and difficult, oppressive. But other times, you are glad for the details you observe: there is something new in each moment, if you can be open to it, aware enough to slow down and exist in the moments of the movement.

Ozeki is interested in the expansion of small details: she offers appendices and footnotes, asking for the reader’s patience. Concision is not her game, and this makes the book better. Its pace is considered and wise, just like the characters she introduces us to.

George Saunders: Tenth of December

“Death very much on my mind tonight, future reader. Can it be true? That I will die? That Pam, kids will die? Is awful. Why were we put here, so inclined to love, when end of our story = death? That harsh. That cruel. Do not like.

Note to self: try harder, in all things, to be better person.”

Tenth of December is a perfect day at the beach — this photo was taken at Wrightsville Beach, near Wilmington, North Carolina, where I lived for three years while earning my MFA. When I picked up this book, I knew it would be great, because while I lived in Wilmington, I sometimes had hard days, and when that happened, I drove to Barnes and Noble and read Saunders, because he asks giant existential questions couched in fascinating worlds and surrounded on all sides by an incredible sense of humor.

It’s like going to your beach in the summer: you know, before you arrive, before you even decide to go, that your friends will be their lovely selves, and the sand will be hot, and the water pleasant. You know that there will be families playing around you and wizened men fishing off the pier and that it will be a drag to park, which will only make the time on the beach sweeter. And when you leave, sand in your hair, sun-kissed and perfectly tired, that’s how I felt when I left the bookstore after reading Saunders: back to being fully in my life, just as I knew I would when I walked in.

Nic Pizzolatto: Galveston

“We come here to tell stories so that we can manage the past without being swallowed by it.”

Galveston, the first novel by Nic Pizzolatto, better known as the executive producer of True Detective, is brussels sprouts. It was a book I expected to dislike. My prejudice came from several places: first, this read was for book club, and I haven’t liked the last two books, so, patterns. Second, the beginning of the book is pretty hard-boiled, a little rote. I didn’t find it as engaging as I would have liked: another white male criminal wants to tell his life story? Um, yawn. But it wasn’t long before I realized that while this is not my favorite book, there’s more depth to this noir than to so many I’ve read in the last few years, particularly Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge (scandalous, I know).

When I was a kid, I couldn’t bear the smell of brussels sprouts, to say nothing of their flavor. I remember crying at the dinner table, heartbroken by their presence on my plate, willing them away. But now, I really love a good roasted brussels sprout. The flavor is meaty and rich, sweet and complex, just like the characters that seem, on their faces, rather one dimensional at the outset of Galveston.

Claudia Rankine: Citizen

“Yes officer rolled around on my tongue, which grew out of a bell that could never ring because its emergency was a tolling I was meant to swallow.”

Citizen is a glass of water. The language is clean and clear, and you can not live without this book. At a time when being white feels like some kind of guilty accident of birth, Citizen is a lesson in reality. This book is beautiful, like a glass of water after a hard workout, unpretentious but sure of itself, of its need to quench you, to offer you what you need to go on, which right now is a lot.

Rankine offers her readers a picture clearer than the video footage that didn’t affect change, and the protests that have yet to affect change, and even a constitution whose amendments seem to bear little resemblance, at times, to the actual world we inhabit.

This book has been necessary always, and it is necessary now. This conversation has been necessary always, and it is necessary now. If we – white Americans who recognize our privilege – are not talking, then we are failing. If we aren’t voting, holding signs, as angry as we’ve ever been, then we are failing.

Thomas Pynchon: Bleeding Edge

“Later those who were here will remember mostly how vertical it all was. The stairwells, the elevators, the atria, the shadows that seem to plunge from overhead in repeated assaults on the gatherings and ungatherings beneath … the dancers semi-stunned, out under the strobing, not dancing exactly, more like standing in one place and moving up and down in time to the music.”

Bleeding Edge is a fistfight – this photo is obviously taken from the iconic movie Fight Club, but it could be any fistfight. Fights typically have a long, boring ramp-up where the two involved parties have a lot to say to each other and a lot of bogus defenses. The fighting doesn’t start for a long time, usually, and it lasts only a moment, before someone calls the cops or one party backs off or stays down.

Bleeding Edge has a huge ramp-up, and I mean that in the worst way. I know people love Pynchon and maybe this is inflammatory, but to my mind, if you mention in the VERY FIRST LINE that it’s Spring 2001, and in the VERY FIRST PARAGRAPH that we’re in New York City, the reader is automatically waiting for 9/11. Why make her wait 315 pages for it?

That’s only one of many criticisms I have for this book, though. Like a fistfight, it offers a lot of action without a lot of actual communication – all talk, like the ramp-up to a fight. If I have to read one more post-modern noir written in present tense, I’ll be the one fighting. It’s not that it can’t be done ever, it’s just that there’s so little room for reflection, introspection. There’s so little space (in this book, actually, no space) to create sympathetic, smart, deep characters. I’ve read and enjoyed other novels by Pynchon, but this one was a big miss.

Sandra Hurtes: The Ambivalent Memoirist

“It appears that no matter where I am or when it is, I’m always searching for a way to bring my inner and outer edges closer together.”

A few months ago, I got an email from Sandra Hurtes. I hadn’t heard from her in a while, and now I can’t even remember how we met. I know it was in 2010, after I’d graduated from college and during the year I was applying to graduate school. Sandra asked me to give a reading, which took place on a freezing night on the east side, inconvenient for almost all of my friends to get to, and yet they did: my friends filled the place, and I was so proud to know them, so grateful for their support.

Sandra asked me to review The Ambivalent Memoirist. The book is like a trifle: a little bit of everything, surprising in its sweetness, presented in a particular way, like a dessert you’ve waited the whole meal for, like you’ve been gazing at it for quite some time. Maybe all the flavors don’t feel quite perfect together, but the unexpectedness is part of its charm — whatever might be missing can be forgiven, even if you can’t eat the entire serving.

It was pretty early in my writing career that Sandra came into my life, and she had such nice things to say about my work. I’m so grateful for her support and the support of so many others who have been my cheerleaders for such a long time now.

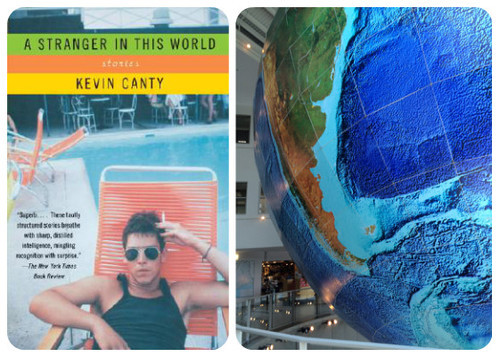

Kevin Canty: A Stranger In This World

“This is my life, she thinks, this is my only life and you’ve taken all of it. Before she knows what she is doing, she draws back her open hand and slaps her son across the cheek, not hard.”

Kevin Canty’s short story collection A Stranger In This World is a globe, like this one, a giant globe in Maine, maybe the biggest globe in the world, that uses satellite imaging at the Delorme store. It’s a collection of stories about people who are spinning out, realizing what their lives – and the lives of those around them – are or aren’t worth. And isn’t this the way? We turn through our days, because we can do nothing else but keep living, keep waiting for the sun to fall and then rise again, and grit our teeth even as we’re working toward something.

I’d read the story Dogs long before I read the rest of this collection, and I marveled at how adeptly it used the second person, how it made me want to weep in spite of its small number of words. The rest of this collection was the same, desperate and powerful, hurtling the reader forward because, like our planet, there is no other option.

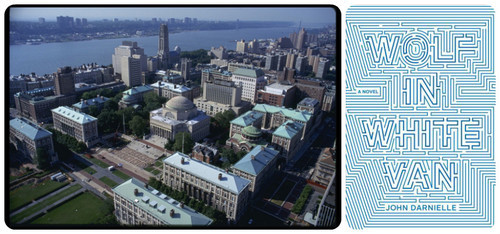

John Darnielle: Wolf in White Van

“It’s really just simple math, the whole of it. There are only two stories: either you go forward or you die. But it’s very hard to die, because all the turns pointing that way open up onto new ones, and you have to make the wrong choice enough times to really mean it.”

Wolf in White Van is learning a new place, particularly, for me, a college campus. I finished my undergraduate degree at Columbia, pictured here, and when you walk into half the buildings, you think you’re on the first floor, but you’re really on the third, and the first floor is some basement that most people have never seen.

Wolf in White Van is a story that shows you the way, taking you incrementally through its pieces, offering the reader enough to feel ravenous for more without being frustrated by the obvious control Darnielle holds onto. I’ve wanted to read this book since it came out, because I am a huge fan of The Mountain Goats, and it did not disappoint.

I wanted, at first, to compare this book to The Legend of Zelda, but that was too easy, so let me just say: this book is doing so much, asking so many things at once, allowing the reader to lose herself in the most interesting ways, for the sake of the journey, like in Zelda, where some ends are not ends at all, and I think that’s what Darnielle is saying, above all. It’s also worth noting that I wanted to compare this book to Joe Worthen’s as yet unpublished but amazing novel, Mezacht, and so as I was reading it, at least for the first seventy-five pages, I just imagined it in his voice and it became like a home for me, when many things in my new home still feel a little uncomfortable, a little too formal.

Bill Bryson: The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid

“Drive anywhere in the state those days and what you see are empty towns, empty roads, collapsing barns, boarded farmhouses. Everywhere you go it looks as if you have just missed a terrible contagion, which in a sense I suppose you have.”

Bill Bryson’s memoir The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid is an Elvis Presley cutout. The book is about how great the fifties were for Bryson and his family in Des Moines. In the foreword, Bryson writes, “Growing up was easy. It required no thought or effort on my part. It was going to happen anyway. So what follows isn’t terribly eventful, I’m afraid.”

He’s right. The book is an unabashed navel-gaze at the unabashed happiness Bryson felt, and still feels, at having been a suburban white boy at a time when nearly everyone else was disenfranchised in ways that they are at least less so now. He spends no time on any conflict that isn’t resolved with milk and cookies, never gets into real trouble, and offers the reader no continuity of thought or action to hold onto for the duration of the book. Even the title is a misnomer.

Like an Elvis Presley cutout, the book is all nostalgia and no substance. There were several moments that made me hopeful: the research about farming that Bryson obviously feels passionate about, his grief over corporate expansion and takeover, even his discussion of his father’s career. But no, like cardboard, they all come to nothing in the end.

Elizabeth Strout: Olive Kitteridge

“He wanted to put his arms around her, but she had a darkness that seemed to stand beside her like an acquaintance that would not go away.”

Olive Kitteridge is the first snow, the undisturbed look of it when you wake up and look out the window: it happened. For most people, this is a wonder every year. It signifies something beautiful, something special and significant, something that can never happen again until next winter.

Me? I hate it. The first snow to me is sullen and depressing, a shroud that will hang on for months, a thing that can’t be erased and has to be accommodated, often with associated danger: slipping and sliding, flight delays, concern over driving.

Almost everyone loved Olive Kitteridge. It won a Pulitzer Prize, for God’s sake. I don’t know why I didn’t love it, why it felt like snow, why it seemed too dreary. Sometimes, my teacher Bekki told me, sometimes you just have a closed reading experience, and this book was that way for me.

Lionel Shriver: We Need to Talk About Kevin

“You can call it innocence, or you can call it gullibility, but Celia made the most common mistake of the good-hearted: she assumed that everyone else was just like her.”

We Need to Talk About Kevin is a walk-in refrigerator, chilly from the first sentence to the last. Shriver’s protagonist, Kevin’s mother Eva, affects a clinical tone in her letters, exploring and suffering on the page, but always restrained, always helping the reader along in particular ways: maybe this is why, maybe this is. The careful analysis in the story, so akin to Kevin’s careful planning, shows a relationship that perhaps Eva herself is only marginally aware of.

In spite of the detached tone, though, this book, like a walk-in, holds everything a reader needs to be satisfied: amazingly detailed and complex characters, a thrilling narrative, and a self-awareness that so many books lack. From these materials, Shriver, like a consummate chef, has put together a book that, like the perfect meal, leaves the reader feeling truly sated. This is a restaurant the reader will visit again (and I have, time after time, with similarly delicious results), a place where the components are treated with great respect, used with their best qualities in mind. Shriver’s writing is precise in the best ways, like a single tomato at perfect freshness.

Meg Wolitzer: The Wife

“New York City was a spectacular place in which to take a walk in the middle of the night if you were a young, ambitious, confident man.”

Meg Wolitzer’s The Wife is a store-bought key lime pie. I’ve read other books by Wolitzer, have seen her speak at the Amphitheater at Chautauqua, and have felt moved by her words, spoken and written. This book, though, didn’t carry the weight that I expected after reading The Interestings. It was like bringing home a store bought pie: especially with key lime, you can taste every note that’s just a little off. Store bought key lime pie tastes just slightly too sweet, when you want it to be tart. The efficient coolants in the giant refrigerators result in a tougher whipped cream than you want, though the pie is a cinch to slice.

The Wife was this way, too. It’s still pie—I’ll still eat it, and happily—but it’s as if there’s a sheen over the whole thing. It’s missing something, that extra layer of nuance and depth, that extra push of exceptionally lyrical language or exceptionally complicated characters. Instead, though the ideas are smart and the revelation well-placed, the reader waits, unfulfilled, for that one extra thing.

Hester Kaplan: Unravished

“The pictures came to Tess in disorganized snaps, which was the closest she could come to describing what middle age was really like. The past was all there still, but you weren’t sure how to organize it anymore into a story that made sense.”

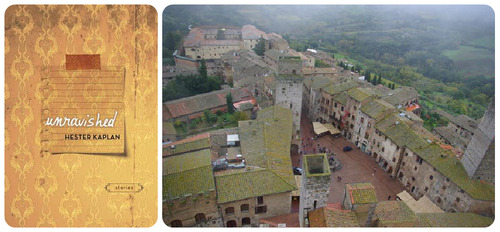

Hester Kaplan’s Unravished is a medieval walled city, like this one, San Gimignano, a tiny city in the Tuscan hills. Walking around the city, like entering this book, you can feel what’s not happening in the present tense narrative: you can feel the history, the backstory. In Unravished, the reader sees what Hester has left out, as careful as Hemingway in her descriptions and omissions. Throughout the book, the reader feels, with great distinction, that the writer is aware of what she isn’t saying, and that the reader’s job is to discern this, to see beneath what she’s presented.

As I walked around San Gimignano, I could imagine, with exciting clarity, what had come in the centuries before my arrival. As I smoked a cigarette with Henry on the steps leading to the duomo, it was simple to imagine all the history I’d missed, all the years that quietly moved, minute by minute, unyieldingly forward, until my arrival. What facility time has, to elasticize just when we need a revelation! It’s the same in Unravished: Hester uses similes with great ease and precision, surprising the reader in all the best ways, letting characters push forward and fall back with language alone. I am so, so excited to be learning from her this fall.

Ann Hood: An Italian Wife

“So this is it, Josephine thought. When we die we do not think of our children who are waiting down the hall, or of the food we’ve cooked to nourish them. We do not think of all the breads we’ve baked, or the tomatoes we’ve grown, or the hours we’ve spent at their sickbeds. We do not think of the things we hoped for. We do not think of the things we loved.

No. It is the things we did not have, the love that broke our hearts, the child we lost, that come to us finally.”

Ann Hood’s new book, An Italian Wife, is Matryoshka dolls, Russian nesting dolls that fit one inside the other. The dolls, like this novel in stories, fit together perfectly, each one adding something to the one before it. Ann’s sense of form, and her ability to work within constraints she sets for herself, is nothing short of genius, and this sense is at play within these fourteen stories as much as in any of her other books.

I try not to make too much noise about how lucky I am to have Ann as my mentor, friend, and sometimes boss, but the truth is that knowing her has actually changed my life. She’s taken me as her nanny to France and Italy, to Portland and Washington and Vermont. And these places have helped to shape me as a writer, and as a person. She has introduced me to so many writers I admire, and she basically got me the teaching job I have now. In return, I prod her child to complete her homework and drive her to ballet. Not a fair deal, but boy am I grateful for it.

The places she’s taken me and the people she’s introduced me to pale in comparison to what I’ve gained from listening to her lectures, though. The most powerful gift she has is how effortless it feels when she communicates her knowledge of form. Even when I’ve heard a lecture before, there’s a nuance the second time that I hadn’t considered previously. There’s always something to hold onto in her lectures, something I can take with me into the pieces I’m working on. There’s no greater joy than hearing a lecture and being spurred to write, and there’s nobody who can elicit that feeling in me the way Ann does.

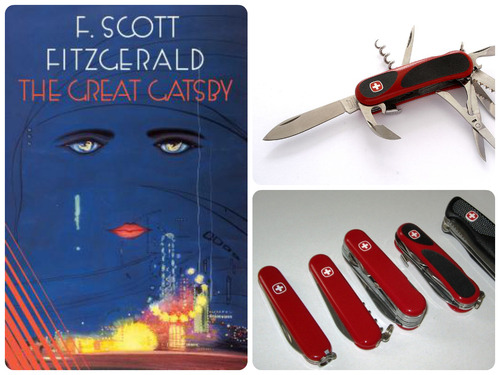

F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Great Gatsby

“Everyone suspects himself of at least one of the cardinal virtues, and this is mine: I am one of the few honest people that I have ever known.”

I don’t normally review books that are uniformly acknowledged to be small acts of perfection. But The Great Gatsby has been on my mind lately, because I’ve been thinking about economy in my own book, and about where to expound and where to pull back. Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is a Swiss Army Knife: everything a reader needs is contained within the book, but each word, like each feature of the knife, is placed so purposefully that such a thing is impossible to duplicate.

When I was not that much younger than I am now, I sometimes held my friends’ Swiss Army Knives, playing with the blades, the corkscrew, that tiny scissors. But often as not, this playing was mindless, and there was always a blade I missed until it was pointed out to me. I bit my nails for a long time, so it was hard for me to work the groove to open it, hard to see it at all.

The first time I read The Great Gatsby, I can’t believe how much I missed. I bet I missed as much this time, though. I bet every time I go back to this book, there will be some new groove, a different sentence that encapsulates the entire book, a different way to read the last line and see how it shines back over the text.

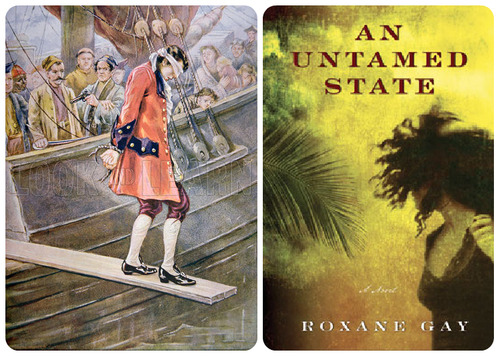

Roxane Gay: An Untamed State

“That’s how I fell asleep, pretending we were in the before, pretending I could still sleep next to him without being choked by terror."

An Untamed State is a walk on the pirate’s plank. The plank is itself a metaphor, of course: it stands in for a certain kind desperation and necessity, the same kind you feel reading this book. Like the protagonist, the reader is held hostage by the narrative, by the aggressive verbs and the aggressive men, by the dread of knowing what’s going to happen and needing to read it to prove to yourself — no, to remind yourself — how scary the world can be.

Walking the plank is not a choice: one is compelled to do so. Typically, sharks or crocs or other dangers lurk just beneath the plank, but behind that narrow strip of wood is the danger everyone lives with all the time, the danger of other humans. And not just other humans, but the danger of inequality, of turning away from what we know to be true because of its inconvenience. Behind us on the plank is a truth we don’t like to look at, because it’s easier to fear a physical danger than to acknowledge the inequalities we may never know how to overcome.

An Untamed State is brutal on the reader, but it is also captivating and important. Read this book. Read it and then recommend it.

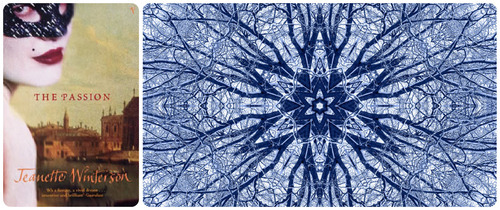

Jeanette Winterson: The Passion

“this morning I smell the oats and I see a little boy watching his reflection in a copper pot he’s polished. His father comes in and laughs and offers him his shaving mirror instead. But in the shaving mirror the boy can only see one face. In the pot he can see all the distortions of his face. He sees many possible faces and so he sees what he might become.”

The Passion is a book about transformation, about perspective, about seeing the same old thing in a new way. What better to symbolize it than a kaleidoscope, whose many facets move, just slightly, again and again, to form new shapes, surprises to the eye. With language that is simple but evocative, lyrical but not unfathomable, Winterson moves the reader through time and space, transitioning easily through gaps that feel cavernous. A kaleidoscope, often, is nothing more than a few beads magnified. But when we twist them, take the narrow view, we see something differently, something new and exhilarating, something we never imagined.

Winterson has been a favorite writer of mine for many years, and all of her books are like this: easy to read but hard to forget. The language is so careful when it’s studied, but effortless to read. I find The Passion humbling for this reason, for the ease with which she takes history and makes it new, just as she does science, or Greek myths, or the Bible, in her other books.

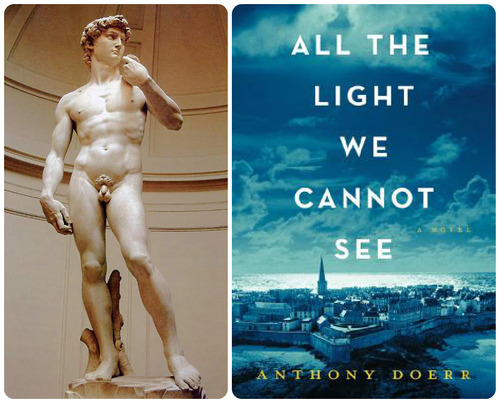

Anthony Doerr: All The Light We Cannot See

“What mazes there are in this world. The branches of trees, the filigree of roots, the matrix of crystals, the streets her father recreated in his models. Mazes in the nodules on murex shells and in the textures of sycamore bark and inside the hollow bones of eagles. none more complicated than the human brain, Etienne would say, what may be the most complex object in existence; one wet kilogram within which spin universes.”

It’s a bold comparison, I know. But Tony Doerr’s All The Light We Cannot See is as exquisite, as breathtaking, as standing before Michelangelo’s David. It’s like this: before you arrive in Florence, before you even plan a trip to Europe, you know that it will be sort of incredible, so you don’t think about it a whole lot, you just know you’ll end up finding it.

I felt that way about All The Light We Cannot See: of course I’m going to read it. I’ve been a big fan of Doerr’s work since I encountered it (and him!) at Chautauqua a few years ago. My dear friend Jen was reading it way back in March, around AWP, and I thought, oh yeah, I’ll have to get my hands on a copy. But it wasn’t until this week that I picked it up: a copy that dear Ann (who also has a new book out!) had Tony sign for me at the Tin House conference I joined her at this summer, taking care of her daughter and playing a lot with Tony’s boys, who were universally adored.

Rarely does a book feel enchanting from its first pages, and even less often does it remain so. Rarely does each weaving storyline feel as engaging as every other, each character drawn as finely and each circumstance necessary. When I felt my small size in front of the David, I felt similarly: that every facet was a small act of perfection, and that every angle was the right angle, and that I could perhaps sustain myself on this work of art alone, because the marvel of it was so deeply satisfying.

Anne Fadiman: Ex Libris

“I have never been able to resist a book about books.”

Ex Libris is your favorite pair of jeans, the ones that fit right, that you don’t have to hitch up or adjust, the ones you reach for even when you know they ought to be washed. I read this book years ago, after I read Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, but before I read At Large and At Small. A teacher recommended it to me, after I turned in an essay for workshop about combining libraries. I abandoned the essay after I read Fadiman’s on the same subject.

Like Fadiman, books about books are some of my favorites. But if I designed clothing — luxury denim, let’s say — I bet that walking through a storage unit of well-made clothing would give me the same rush, the same excitement. Finding that pair of jeans in the store is relief enough as a consumer, but as a writer, reading Fadiman’s thoughts about books and learning feels so electric as to seem almost forbidden. A favorite pair of jeans is with you all the time: as you’re laughing with your friends and flying across the country, when you’re going to meet new people and when you’re not sure if you’re underdressed.

I carry Fadiman this way: in my mind whenever I teach a class and when I’m remembering my own childhood. When I lend a book but request it back soon, when I tell someone what they “just have to read,” and when I want to correct the punctuation or spelling on signs and menus. What luck, to have someone else articulate so clearly, and with such wit, how I feel about language, about the joy of reading, about being a writer in this world.

Brian Evenson: Windeye

“The dilemma was all around him, solid as architecture, like a structure he was forced to live in or a cage that was locked around his head.”

Windeye is a seven course dinner, delicious and indulgent and with only a few flavors not to your taste, as if the chef had mostly intuited your palate. Evenson’s stories, of which there are an incredible twenty-five in this collection, are mostly short and horrifying and quick to draw the reader in. They read like folklore and also like beautiful warnings. But like a huge meal, it is easy to feel full too soon, and to go on in spite of the body’s exhaustion, adding flavor to flavor until each feels just a little duller than the explosion of the first taste. The stories at the beginning and end of this book are heroic, probing deep into the senses. But in the middle, I wished some stories had more length or explanation. From time to time I eat meals like this, many courses long, and while I appreciate the distinction of each plate, I sometimes wish for more of a single dish. A little more risotto, a little less fennel. That said, dessert, when it comes, is always a pleasure and a relief, and these stories will stay with me a long time, just like those meals. Best of all: they’re great for teaching!

Muriel Spark: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

“Give me a girl at an impressionable age and she is mine for life.“

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie is a really smart puppy. More specifically, a really smart puppy who knows that he’s done something wrong. Spark’s prose is nuanced and funny and delicate, and because of this, the reader finds Miss Brodie utterly sympathetic, in spite of her many shortcomings. So lulled was I by the careful sentences, the well-rendered narrative, that I began the book wholly in her corner, and it wasn’t until much later that I realized the true danger of a character like her.

If you’ve ever raised a puppy, especially a smart one, you know exactly what I mean. Puppies are so cute it’s easy to forgive all the terrible things they do. Even if you sometimes suspect your dog might be a little smarter, or a little more conniving than you, or at least than you give him credit for, you think, but look at that tiny face! Those big eyes! Just like Muriel Spark, your dog is forcing you to love him and then turning the tables of the story, pulling on his leash or ruining your carpet or pretending like he doesn’t know the command you’ve called.

Anita Brookner: Hotel du Lac

“The day seemed interminable, yet neither was in a hurry to have done with it. It seemed to both of them in their separate ways that only the possession of this day held worse days at bay, that, for each of them, the seriousness of their respective predicaments had so far been material for satire or for ridicule or even for amusement.”

Hotel du Lac is a pair of neon bike shorts, circa 1985. It’s true, this color, if not this particular style, is coming back. It’s seeping into our workout clothes first, and maybe soon we’ll be teasing our hair again too. But when I think of the 1980s, it’s Madonna’s lace and neon and big hair that come to mind: they represent a particularity. So does Hotel du Lac: for a piece of contemporary fiction, it calls back to Faulkner, with long descriptive passages that don’t matter to the central plot. Brookner uses, as you can see above, and as I’m attempting here, many, many commas, and a lot of punctuation in general. She doesn’t care if the reader doesn’t have a scene for five or six pages. She doesn’t care that she hasn’t mentioned the time period in the first twenty pages, and it could be 1940 or 1975. It’s a time of plenty, and Brookner is indulging, and while it didn’t work for me in 2014, it won her the Booker prize in 1984.

Lacy M Johnson: The Other Side

“After we hang up there is only silence. There’s only darkness lapping at the window. There’s only an empty page on the screen.

Only the story can bridge it.”

Lacy Johnson’s memoir, The Other Side, is the glass shards sometimes used in lieu of barbed wire as a security measure on top of walls. In other words, it is incredibly beautiful, but it will fuck you up. I first saw this type of security when I was 19, walking around New Orleans with a boyfriend as we drove around the United States, tough and despondent and hard to impress. But the glass, so beautiful and dangerous, impressed me. It’s been over a decade since then, and when I picked up Lacy’s book, it was with a little trepidation: I knew the facts and was nervous to read the details, alone in a new house in a new town in a new state. But once I began reading, I could not put this book down. Like the glass, this book is rendered in beautiful pieces, vignettes that together build a narrative. And at the end of the book, I felt torn open, and hopeful, and all of the complicated feelings I love at the end of a great, hard book. I met Lacy this summer in Oregon, and when she signed my book, she wrote, “Open the door.” I’m glad I did.

Ann Patchett: Bel Canto

“Not everyone can be the artist. There have to be those who witness the art, who love and appreciate what they have been privileged to see.”

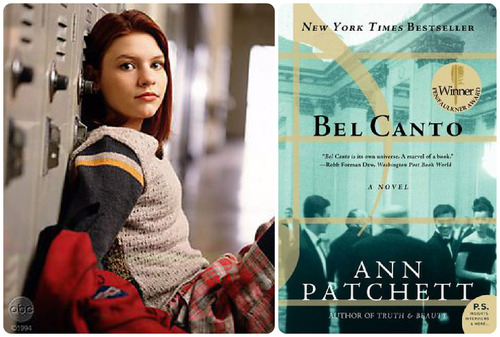

Bel Canto is Angela Chase. You remember her, Clare Danes playing her on My So-Called Life, the show everyone who was a teenager in the nineties has been missing and discussing since its first and only season. Angela was the star, glum and excitable and as misunderstood as any teenager.

The characters in Bel Canto are the same: complicated and fully themselves, unapologetic for their actions and beliefs, plagued by doubt but outwardly sure of themselves. I loved this book for its metaphors, its belief that what seems wrong might be right, and what seems right might be misdirected. I loved it the way I loved Angela Chase’s wrong moves, and wrong thoughts, the way she kept after Jordan Catalano even though he was a jerk.

Angela was our witness to being a teenager, and Ann Patchett is a witness too, to the larger conflicts we didn’t know about back then, when the boy and the hair and the clothes were most important. Ann Patchett is calling our attention to what is necessary and complicated now, and we must heed that call with as much devotion as we had to Angela.

Audrey Niffenegger: The Time Traveler’s Wife

“I wish for a moment that time would lift me out of this day, and into some more benign one. But then I feel guilty for wanting to avoid the sadness; dead people need us to remember them, even if it eats us, even if all we can do is say "I’m sorry” until it is as meaningless air.“

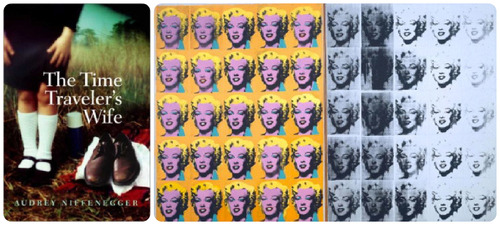

The Time Traveler’s Wife is Andy Warhol's Marilyn Monroe diptych. With each new face, we notice a slight difference, something that makes the image unique. And each time Clare is faced with the reality of her husband, her lover, her friend, she must react in a slightly different way in order for the novel to work.

The complications of marriage, of character, are thrown into relief by the impossibility of the situation. We rely on magical realism to show us something we couldn’t – or wouldn’t – see otherwise. SImilarly, by "mass-producing” the Marilyn diptych, Warhol asks his viewer about the complications of art, of replication, of wanting the thing that hangs in that museum, even if it’s a cheap printed copy.

Rebecca Skloot: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

“I’ve tried to imagine how she’d feel knowing that her cells went up in the first space missions to see what would happen to human cells in zero gravity, or that they helped with some of the most important advances in medicine: the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization. I’m pretty sure that she—like most of us—would be shocked to hear that there are trillions more of her cells growing in laboratories now than there ever were in her body.”

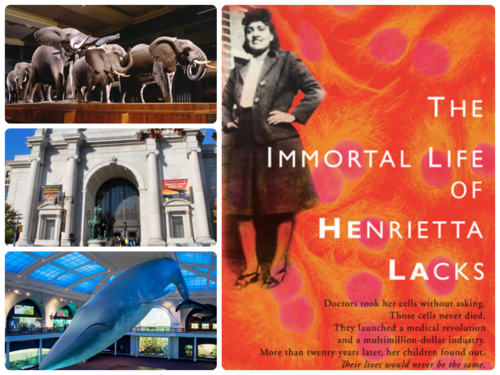

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is a museum you know really well. In my case, that’s the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, situated just west of Central Park. For one year, after I finished my bachelor’s degree and before I started grad school, I was a nanny for an eight-year-old girl who wanted nothing more every day than to visit the butterflies who grace the museum every winter. When you know a museum well, entering it feels not so intimidating: you know you’ll take a sharp right and head up the stairs, instead of wandering through the mammals a while before you make it to the butterflies, which is all you’d come to see today.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks quickly feels familiar, even though it’s a book of ideas, a book that asks big questions about the future of medicine, about what a life is worth. Skloot weaves deeply researched narrative beautifully into the book, pumping its heart with personal stories, with herself, implicated by her curiosity. It’s not that different from standing before The Squid And The Whale, remembering when you were there last, adding a story behind the story, wondering what it means, what you can do. You’re just one small person in front of something big, something that might mean the whole world. It’s important to put ourselves in this position, as writers and as readers. We have to think about the whole world, and about the choices that are complicated and messy, and how to accept or refuse to accept them. Stepping into a book — or museum — that feels like a home is one way to feel safe thinking about the big issues.

And, full disclosure, my greatest hope is that someday my books will sit right near hers on a shelf: Sklar, Skloot — the only person between us might be her dad, Floyd Skloot. I can live with that.

Interlude: Literary Blog Tour

Hannah asked if I’d be willing to participate in the Literary Blog Tour, and of course I agreed, so I’m sacrificing today’s book review in favor of a little exploration of my own process. Below my answers, you’ll see links to the websites of four writers I know and love, who will answer these same questions on their blogs soon.

1. What are you working on?

I’m working on the second draft of a novel. I earned an MFA in creative nonfiction, and the novel is a complete shock to me – I never attempted to write fiction until last summer, because I always believed myself to be fundamentally not that creative, not capable of inventing a whole world, a whole cast of characters, a whole set of circumstances under which they must live. The book began when I was cheating on my thesis, a memoir that is now sitting in a drawer for the foreseeable future.

2. How does your work differ from others’ work in the same genre?

Good question! Does it? I’d classify my novel, about an invisible girl, as magical realism, but I’m not sure it differs dramatically from other books with the same classification. I’m of course partial to my characters, especially the grouchy little brother, but I feel that the novel fits pretty squarely into the magical realistic world.

3. Why do you write what you do?

Sometimes you get an idea and you just know: this is what I need right now. Sometimes it doesn’t make sense, and why should it? What has ever made sense, in your life? You are infamous (notorious, even?) for “following your heart,” and for doing what “feels right,” and even though you’re not totally sure what those phrases even mean, especially in the context of creative output, you’re aware that this is the thing that has called you, and you will answer that call.

4. How does your writing process work?

When I’m producing, I write 1,000 words a day, every day, even when it hurts, even when they’re bad, even when I don’t feel like it, even when it’s my birthday. I do this not because I believe it’s great to write 1,000 shitty words, but because I believe that if I skip a day, then I might skip a second day. Discipline is a practice, and art requires discipline, and although I manage it for long stretches, I know how easy it is to fall off, to go to the beach instead, to have fun and decide to do it tomorrow. Tomorrow might end up being next week or next month, and I want this book in the world.

When i’m revising, it’s different. I try to work a few hours a day, but it is exhausting, difficult work, and so I cut myself more slack during the revision process. Right now, I’ve been trying to revise one chapter per day, leaving post-it notes and marking in a separate file what is outstanding in each chapter: I change a lot and leave some scenes to write or fix up before I hand off the draft to my trusted readers.

Remember to check out the following four amazing, intelligent women writers below for more thoughts on this and other important things you want to know.

Ana Cristina Alvarez is a recent MFA grad from UNCW, and is also a writer, typesetter, designer, and coffee whisperer. She also bakes a hell of a flan.

Michelle Crouch lives in North Carolina. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Gigantic Sequins, Indiana Review, Weave Magazine, and others.

Kathleen Jones lives and works as a teacher and designer in Wilmington, NC. She holds a newly-minted MFA in poetry from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. Her work most recently appeared inStirring: A Literary Collection and Gesture and is forthcoming in Ninth Letter Online, Heavy Feather Review, Baldhip, and Middle Gray.

Elise Blackwell: Hunger

“Instruments were placed on the stage’s many empty seats, both a tribute to the dead and a suggestion of fuller sound. I stared at an orphaned piccolo as the first movement began its savage march.”

Hunger is a modern living room: sleek and spare, made mostly of metal and leather, of materials that don’t break down easily into their component parts. It’s a novel that feels sturdy and thick, but in fact, it’s tiny. Dense, but tiny — well under 200 pages, in fact. A modern living room doesn’t announce itself, like the characters in this book: they are present and fully realized, but drawn with the precision of a designer couch, a lamp that curves just so.

I don’t love the modern living room, but I can appreciate the lines, the style, the ambition to make a piece of furniture functional and beautiful at once without a lot of flourish. And yet, though a novel rich in emotion is also a joy to read, the implication of feeling remains, both in Hunger and in the living room: clearly, the viewer can experience what’s missing, what might be said, what hopes and fears remain long after the designer — or writer — has left the creation.

Michael Cunningham: By Nightfall

“Isn’t this part of what you keep looking for in art – rescue from solitude and subjectivity; the sense of company in history and the greater world; the human mystery simultaneously illuminated and deepened: by Giotto’s expelled Adam and Eve, by Rembrandt’s final self-portraits, by Walker Evans’s photos from Hale County. The art of the past tried to give us something like what’s happening to Peter right now – a look into the depths of the human other.”

By Nightfall is a sea anemone, one that can fold into itself when threatened, but that also opens up like a gift, like an offering to the reader. On its face, the book is almost plain, like an anemone hidden inside of itself: the story, of New Yorkers being themselves, living their daily lives on the streets, in the art world, neurotic and sad and bold, is unremarkable in many ways.

It is the quality of prose, the sounds and word pairings, that make this book unfurl so beautifully. Again and again, Cunningham uses italics to great effect, uses particular phrases and images that strike the reader harder each time instead of losing their power. The writing about art, especially, is beautiful, timeless, haunting, like an anemone swaying in place: we know it will be there when we come back. We have faith that it will stay put, that the qualities our protagonist is searching for will be the ones people search for a thousand years from now, and that a thousand years ago, that essential search was the same.

Leslie Jamison: The Empathy Exams

“I think the possibility of fetishizing pain is no reason to stop representing it. Pain that gets performed is still pain. Pain turned trite is still pain. I think the charges of cliche and performance offer our closed hearts too many alibis, and I want our hearts to be open. I just wrote that. I want our hearts to be open. I mean it.”

The Empathy Exams is an underground cave, one you have to squirm and crawl into, but that opens up into an unexpectedly large space once you’ve done the hard work of entrance. The essays of this collection are smart and delicate, academically rigorous but full of heart. There are shocking, beautiful images all over the place. Jamison asks the reader for the impossible: look into the thing you fight against and embrace it – no, don’t embrace it. Embody it, envelop it, accept it as a very part of yourself.

Each of these essays enters an idea through an object or subject, and then expands, like a cave you can hardly believe is there, when you find an opening that is a mere crack in a sheer rock face. When you come out the other end of the essay, though, it’s not far away at all from that initial crevice. That’s how tightly wrapped these essays are: whatever you leave outside, it will be right there when you emerge. The thing that’s moved is you.

Aimee Bender: An Invisible Sign of My Own

“Some worries sit in the stomach like old bad food. Most of the time, they are so quiet and dormant you can’t feel them at all. Oh good, you might think. They’re gone.”

An Invisible Sign of My Own is a hedge maze: this one is at Longleat Amusement Park in the UK. A hedge maze is a thing of beauty, made to confuse and inspire awe at the same time. If only, when inside of it, one could see it from above: it would be obvious which way to turn. But if we wanted to know which way to turn, we never would have entered the maze in the first place. Bender’s main character, Mona, asks the reader plainly: what are your intentions for this life? How will you make sense of all the senselessness we have to face every day?

I have been thankful for this book each time I’ve read it: first, when I was just a few years older than Mona Gray, and just a little bit less confused; second, when I was in love with someone who reminded me too much of her; and third, this week, when I feel, for the first time, like I’m looking down at the maze, like I’ve made the proper turns and, though there are still more to make, that I can do it with confidence. I know the maze is still around me, but I’m not afraid of it the way I was the first time I read An Invisible Sign of My Own. I’m excited to make my way through it, excited to choose left, not right, excited that no matter what, the sky will always be above me: that there are some things, like Mona’s numbers, that we can always depend on.

Nicole Krauss: The History of Love

“He learned to live with the truth. Not to accept it, but to live with it. It was like living with an elephant. His room was tiny and every morning he had to squeeze around the truth just to get to the bathroom. To reach the armoire to get a pair of underpants he had to crawl under the truth, praying it wouldn’t choose that moment to sit on his face. At night, when he closed his eyes, he felt it looming above him.”

The History of Love is a fifty meter swimming pool, like this one, which I swam in only once while in France, amazed by its length even though I knew it was double what I was used to. I’d seen it from the inside pool, the twenty-five meter one, when it was empty and while it was being cleaned and then filled with water but not yet ready for swimming.

The History of Love appeared to me before this week lots of times: I read the beginning while visiting a friend years ago, but didn’t have time to finish it and couldn’t take it with me. What I didn’t expect, from the book or the pool, is how quickly I’d be in deep, unable to stand or bear the weight of my own feelings. In the middle of the pool, I realized how long there was still to go before I reached the end – and that once I got there, I wouldn’t be able to stand. It wasn’t twenty pages into Krauss’s novel that I realized a similar thing: that she had a crafted a book that contains such beauty and pain that it’s hard to stand up in, hard to find the bottom of, hard to pull oneself out from.

Hannah told me I had to read this book “Right. Now.” when I told her that my novel’s working title was also the title of a book written by one of the novel’s characters. And while she was right – I did need The History of Love this week – she was right not because of any similarity to my book, but because I needed something beautiful and immersive, and this was just the thing. The best part about living among many, many writers? Someone put the book in my hands moments after our conversation.

Andrea Barrett: Ship Fever

“You ought not lie down and let your fate roll over you, her grandmother taught her; neither ought you stand unbending, as her father had, and wait for fate to lop off your head. There was a bending, weaving, cunning way, in which you appeared to give in but rolled aside just slightly, evading the blow at the last minute… ‘Make your mind like a pond,’ her grandmother had said, when she found Nora weeping at night. ‘Push away longing and fury and make your mind still, like water.”

Ship Fever is an antique mirror set, full of short stories that are curious about the past, about what we can recognize and identify from a time that feels lost. Barrett’s characters are familiar, even though many of them live in a time before we came along. They are like the antique vanity sets you see from time to time — they’re not something we’d go to the store and buy, but we know what to do with them in our hands: comb your hair, look at your face. Barrett asks her reader to do the same work that an antique vanity set does: look here, she says. This character is suffering the same way you’ve suffered. This character is living with something you may never have lived with but have you not lived with something else? You have, she says, thrusting the mirror in the reader’s face.

And Barrett’s right: when we look into the hearts of these characters, we are simply looking at ourselves, drawn in ways we wouldn’t think to draw ourselves, but no less true because of that.

Fiona McFarlane: The Night Guest

“It came to her that she missed her children, not as they were now, with their own children, but as they had been when they were young. She would never see them again.”

The Night Guest is a very old computer. Do you remember approaching the first computer you saw? I do: I remember looking at it and wondering what was inside, how it worked, whether I’d be able to make things happen by using my fingers and my eyes. Conceptually, it was a marvel, and The Night Guest is a conceptual marvel, too. McFarlane introduces beautiful questions and asks the reader to think them through. The sections about the tiger stood out not just because they were surprising, but because the writing in those sections was the most compelling of the book.

I don’t know about you, but the first time I actually sat down to a computer, it didn’t do much of anything. In spite of what it could have done, if I’d had the wits or the know-how, it became boring in moments, when I realized all I’d actually be doing on it was writing words. I could already do that on paper. The cast of The Night Guest was hard for me to care a lot about, and though the prose was excellent in some places, I probably wouldn’t have finished it if not for book club.

Chad Harbach: The Art of Fielding

“There were no words for that, no ceremony that would garantee your future. Every day was just that: a day, a blank, a nothing, in which you had to invent yourself and your friendship from scratch. The weight of everything you’d ever done was nothing. It could all vanish just like that. Just like this.”

The Art of Fielding is Mt. Blanc, situated just above Chamonix, where I’m close to finishing the first draft of my novel, where there is still snow at the end of June, where the city is nestled between mountains, full of adventurous people and now, new friends. For four weeks, I’ve been looking out at this mountain from different angles: from the top of the lift at Flegere, and as I hiked from there to Planpraz, and as I came back down on a cable car. From the balconies and skylights and windows and front doors of the five, soon to be six places I’ve stayed while in this town. From the air, after I jumped off a cliff to paraglide back to the earth.